To the Real Challenge: Selling It

The norm at Terra Nova is that I’m editing books and publishing books written by other people. But now I’ve published a book that I wrote myself (though edited by someone else, of course). It feels like an unusual hat to have on.

This book has come to be because of a powerful force acting on me. That force is named New Mexico. It’s the state I’ve lived in for thirty-one of the past thirty-eight years. Somehow, over that time, it has spread tentacles that seized and entrapped my inner feelings.

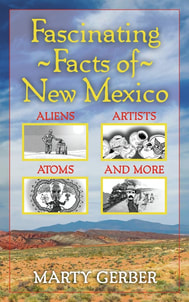

If you’d like an idea of what specifically those tentacles consist of, sorry but you’ll have to buy the book. It’s titled Fascinating Facts of New Mexico, and it’s available at your local bookstore or via cyberspace from some outfit named after a river, but I forget which. (Maybe it’s the Danube or Nile or Monongahela.)

But generally speaking, what’s behind the book is the fact that I simply became so fascinated by the state’s people and places and stories as I learned more and more about them—and since most of those thirty-one years were spent in the newspaper business, I came to learn a great deal. It’s information that adds a real fullness to my life in New Mexico, and it inspires me to share some of that fullness with others. It’s a gift I love to share—and to receive in return the next person’s intriguing and unexpected knowledge of the state.

So now I’m a “published author.” And though I was obviously spared some authors’ ordeal with their editor and/or publisher, I’m not spared those authors’ confrontation with the marketplace. The same eight hundred new books published every day that every other author is up against is aiming to shove me into the remainder bin as well.

How can I survive? How can I convince the 173 million U.S. book readers (or a reasonable percentage thereof) to choose my book over anyone else’s? The answer I’ve always told Terra Nova authors is “marketing.” And if I didn’t already know it, I’d tell it to myself now.

I sit here at my computer having been “launched”--personally--into the world of appearances, interviews, tweets, reviews, Facebook, articles, signings, readings, blogs, press releases, etc/etc/etc. And it feels like a good world to be in for me, with powerful reward from both the enthusiastic response readers are giving Fascinating Facts, and from knowing I’m doing the max to help myself, in the super-tough job of connecting a book with readers.

So yeah, as I noted upfront, having an author’s hat on feels a little strange. But that doesn’t make it a bad thing at all. It simply means I’ve moved from one kind of challenge to another. What else is life here for anyway?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed